Petra: The Rose-Red City Carved from Memory and Stone.

Petra is a city that arrives slowly. You do not see it; you feel it first. Heat rising from the desert floor. Wind whispering along rock worn smooth by centuries of hooves and footsteps. The faint scent of dust, sun-baked and ancient. A hush gathers as the path narrows, drawing you into the darkened mouth of the Siq, a canyon not carved by people but by water, earthquake and time.

It is a fitting entrance to a place built on silence and spectacle. Petra was never designed to announce itself from afar. It reveals itself like a story, turning page by page, bend by bend, until the walls around you tighten and shadows swallow the light.

Inside the Siq, the world compresses. The sandstone rises in waves of red, gold, pink and ash, striations twisting like the inside of a seashell. At your feet, channels cut into the stone run alongside the path, part of the Nabataeans’ genius water system that allowed a city to flourish in a landscape that should never have supported one. Sunlight fractures overhead, thin and distant, as though the sky has been reduced to a single blue ribbon.

The first glimpse of Petra through the Siq, where shadow breaks and stone remembers Petra reveals itself one breath, one footstep, one shard of rose-red stone at a time.

And then, just as the canyon seems ready to close entirely, the stone splits.

A sliver of brightness.

A vertical seam of gold.

A hint of geometry where nature should rule.

You step forward. The slit widens. Columns sharpen. Shadows fall away.

And the Treasury stands before you.

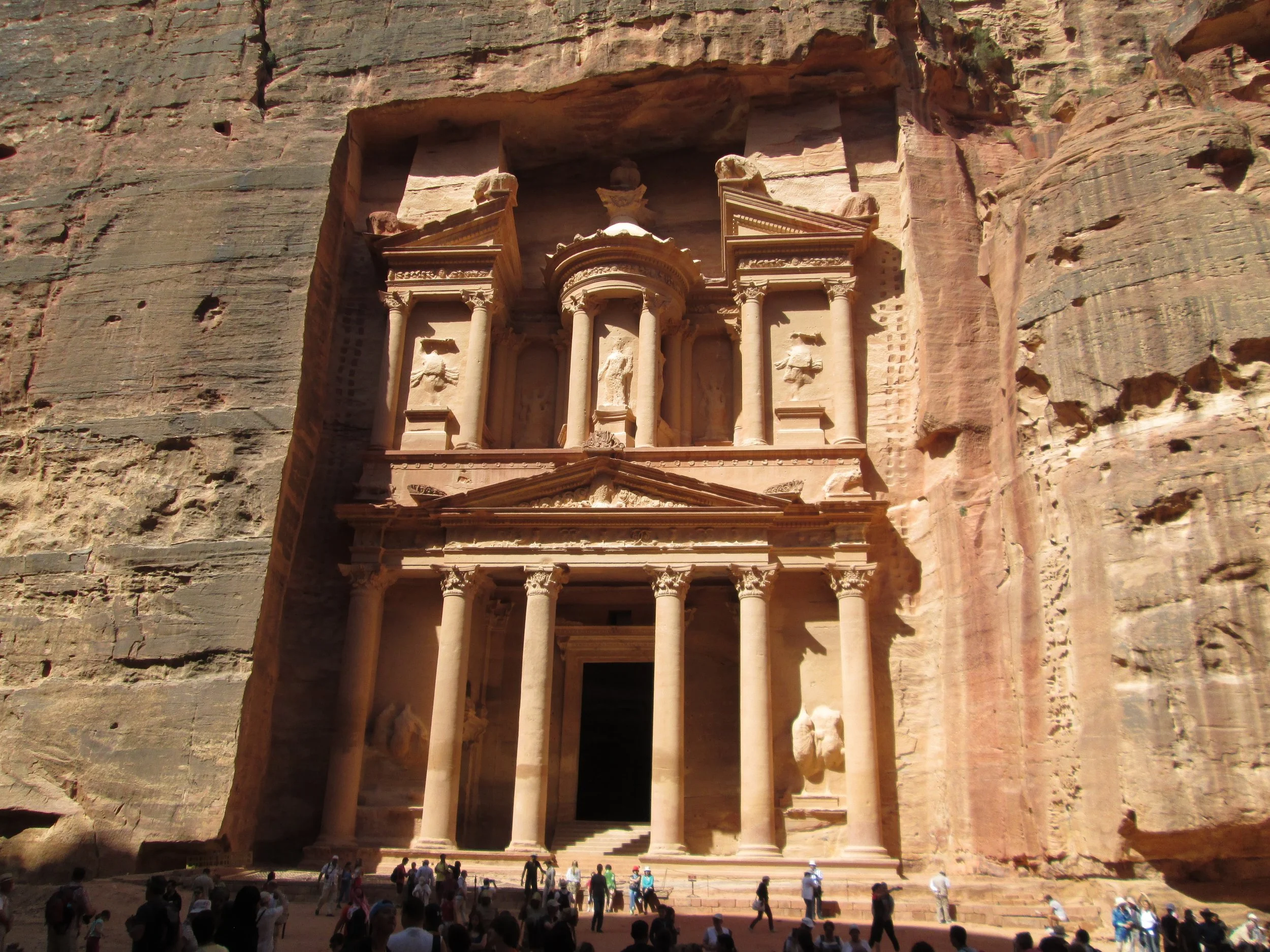

For a moment, nothing exists except that façade. The Khazneh is less a building than an apparition: carved, not built; sculpted directly from the mountain as if the mountain itself chose to imitate a palace. Corinthian columns soar above you. The urn at the top glows pink in the morning light. Every inch of stone bears the memory of chisel marks, wind erosion and ritual.

It is dramatic not because it needs to be, but because the Nabataeans understood theatre. They understood the emotional weight of emergence. After the darkness of the Siq, the Treasury is not simply a monument; it is revelation.

Petra’s most famous icon, aglow in the afternoon sun. Columns, statues, and shadows telling the story of a kingdom that mastered stone the way others mastered a language.

The City Behind the Icon.

Most visitors assume Petra is the Treasury. But it is only the doorway to a world sprawling far beyond what that first glimpse suggests. Behind it, the valley opens wide and the city begins to breathe again.

To the left, tombs cluster along the cliff faces, their façades rising like stone echoes of the Treasury. To the right, the Street of Façades continues into a landscape carved with intent: shrines, niches, offerings, stairways that lead nowhere except imagination.

Further along, the Theatre curves into the rock, an architectural gesture borrowed from the Greeks yet undeniably Nabataean in execution. It once held thousands, a statement that Petra was not simply a place of the dead, but a living capital of trade, ritual and diplomacy. The stage is silent now, but the wind still runs its fingers along the carved seats.

Beyond the Theatre, the valley floor widens again. Columns rise in broken rows along the Colonnaded Street. Foundations of temples, shops and administrative buildings lie scattered like bones. Here stood the heart of the city, a place where incense caravans arrived from Arabia, laden with spices, myrrh and goods destined for distant markets.

The Great Temple, overlooking this stretch of road, is vast even in ruin. Its staircase climbs in terraces. Pillars once held aloft a sanctuary where priests conducted rituals tied to Petra’s deep spiritual landscape, a world shaped by deities like Dushara and al-Uzza. Excavations have revealed mosaics, altars and fragments of decorated capitals, reminders that the city thrived not only materially but artistically.

The Tombs of Kings and Commoners.

Petra is a necropolis as much as a city. Along the cliffs rise the Royal Tombs:

the Urn Tomb, its façade weathered into ripples of red and rust

the Silk Tomb, streaked with colour as if nature had painted it by hand

the Corinthian Tomb, echoing the visual language of the Treasury

the Palace Tomb, sprawling and ambitious

Each one is a statement of rank, wealth and legacy. Yet the Nabataeans buried their dead in hundreds of smaller tombs as well, carved throughout the valley walls. Death in Petra was democratic; memory belonged to everyone.

Inside the tombs, the stone patterns are hypnotic. Swirls of mineral-rich reds and whites wrap the chambers, giving the impression of painted frescoes created without a single brushstroke. Your photographs capture these interiors perfectly, the rippled colours, the soft light and the silence that feels almost sacred.

The Monastery: The City’s High Place.

The climb to the Monastery is a pilgrimage. Hundreds of steps twist up the mountainside, carved unevenly into sandstone smoothed by footfall and rain.

At the top, the landscape opens and the desert drops away in golden waves. The Monastery stands like a titan: larger than the Treasury, more austere, stripped of ornament to reveal sheer scale. It was a tomb, a sanctuary, a place of ritual significance perched at the roof of the city.

Goats wander its threshold. Wind drags heat from the stone. Across the plateau, tea tents offer shade and the long view towards Wadi Araba.

The Monastery feels like a reward earned rather than a sight simply visited.

Far from the crowds and carved on a monumental scale, the Monastery waits for those willing to make the climb.

A City Fed by Water.

The Nabataeans were masters of water. They built Petra not because the landscape was easy, but because they could bend it to their will.

Channels ran along the Siq.

Dams controlled seasonal floods.

Cisterns stored water for months.

Ceramic pipes carried it across the city.

This network did more than sustain life; it enabled agriculture, luxury, trade and ritual in a place that should have been hostile. Their engineering is one of Petra’s greatest achievements, rivalled only by their architecture.

Decline, Rediscovery and the Return of Footsteps.

Petra’s decline came slowly. After the Roman annexation, trade routes shifted. Earthquakes reshaped the city. The population dwindled. By the Middle Ages, it faded into legend, preserved only in local memory until European explorers reached it in the nineteenth century.

Today, the valley fills with voices again: visitors, guides, Bedouin families whose histories weave through the canyons. Footsteps echo where caravans once passed. Horses, camels and donkeys thread the paths, continuing traditions older than any modern nation.

Yet Petra’s challenges remain. Tourism pressures its fragile structures. Weather erosion bites deeper each year. Preservation is a constant negotiation between access and protection.

A City That Remembers.

Petra holds you not through grandeur alone, but through atmosphere.

Through the colour that shifts with every hour.

Through the quiet inside its tombs.

Through the way light touches stone and makes history feel alive again.

It is a place where memory settles like dust, where human hands and natural forces have collaborated across millennia to create something impossible. The city is both ruin and revelation, museum and wilderness, civilisation and silence.

When you walk back through the Siq and the sky widens, it feels as though you have stepped out of a different world. Petra does not leave with you; it stays behind, waiting, as it always has, for the next set of footsteps.