Dunluce Castle: Power on Borrowed Ground.

Dunlace Castle, Stone, sea, and the cost of ambition.

Dunluce Castle does not merely overlook the Antrim coast.

It occupies it on borrowed time.

Perched on a fractured basalt headland above the North Atlantic, Dunluce has always existed in a state of tension. The sea presses in from three sides. The rock beneath it is fissured and unstable. From the moment the first defences were raised here, the castle’s greatest strength and greatest weakness were the same thing.

This is not a ruin shaped only by history.

It is a ruin shaped by geology.

Origins: A Castle Before a Clan.

This was always borrowed ground.

The site at Dunluce was fortified as early as the 13th century, likely by the Anglo-Norman de Burgh family, who were expanding their control across Ulster following the Norman invasion of Ireland. At this stage, the castle was smaller, simpler, and primarily defensive.

What made Dunluce valuable was its position. The narrow land bridge connecting it to the mainland meant that a small force could hold it against a much larger one. Supplies could arrive by sea. Retreat inland was unnecessary. Control of this headland meant control of the surrounding coast.

But Dunluce would not remain in Norman hands for long.

The MacQuillans and the Lords of the Route.

The inner courtyard, open to all elements.

By the late medieval period, Dunluce had become the stronghold of the MacQuillan family, Gaelic lords who controlled much of what is now north Antrim. The MacQuillans were not merely local rulers. They were gatekeepers of a maritime corridor linking Ireland to western Scotland.

From Dunluce, they levied tolls, enforced authority, and engaged in constant skirmishing with rival clans. The castle was not an isolated fortress but the centre of a power network that depended on ships, not roads.

Life inside the walls was hard and exposed. The courtyard you see today once held workshops, stores, and living quarters. Every aspect of daily life was shaped by wind, salt, and the proximity of the sea.

Conquest by Kin: The MacDonnells Arrive.

The stone bridge across the chasm.

In the early 16th century, Dunluce changed hands through violence and strategy rather than inheritance. The MacDonnells, a powerful Scottish clan with ancestral ties to Ireland, seized the castle from the MacQuillans.

This was not an invasion by outsiders. It was a reassertion of kinship power across the North Channel. The MacDonnells ruled Dunluce as Lords of the Glens, strengthening links between Antrim and the Hebrides and turning the castle into a hub of cross-channel politics.

Under the MacDonnells, Dunluce reached its height.

A Seat of International Power.

The ruins and defensive walls.

By the late 16th century, Dunluce was no longer just a regional stronghold. It was entangled in European conflict. Sorley Boy MacDonnell, the most famous of the clan’s leaders, played a dangerous game between England, Scotland, and Spain.

After the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, ships wrecked along the Irish coast. Dunluce became a place of refuge and salvage. Cannons recovered from Spanish ships were mounted on the castle walls, giving Dunluce continental firepower.

For a brief period, this clifftop fortress on the edge of Ireland stood at the intersection of global empire.

Collapse and Consequence.

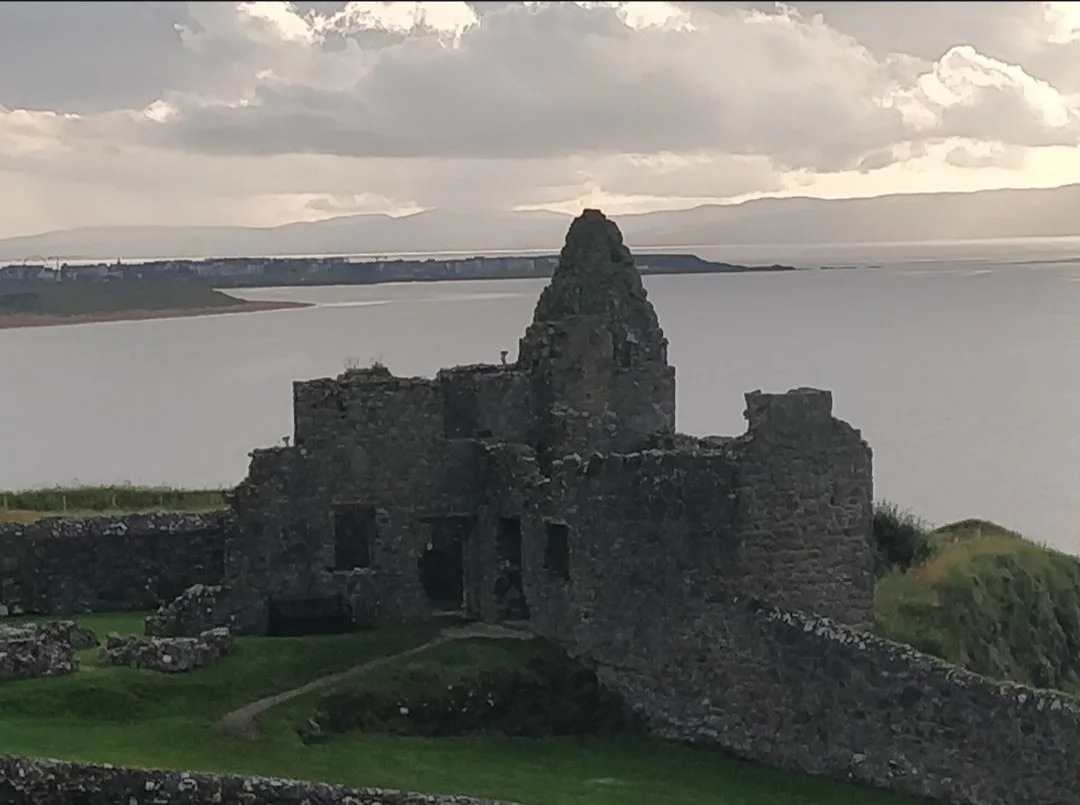

Primary remnants of the inner complex.

In the early 17th century, disaster struck. During a storm, part of the castle collapsed into the sea. Tradition holds that the kitchens fell away, taking servants with them. Only one survived.

Whether exaggerated or not, the collapse was real. The rock beneath the castle had shifted. The sea had breached the defences from below.

From that moment, Dunluce was fundamentally compromised.

Plantation, Decline, and Abandonment.

As English authority tightened its grip on Ulster through the Plantation, the MacDonnells attempted to adapt. Randal MacDonnell, Earl of Antrim, even built a planned town near Dunluce, envisioning a modern settlement to rival any in Ireland.

But the castle itself was no longer viable.

By the mid-1600s, Dunluce was largely abandoned. Power moved inland. The cliff edge continued to erode. What armies had failed to achieve, time and geology completed.

Dunluce in the Shadow of History.

The abandonment of Dunluce in the mid-17th century did not remove it from history. It changed the kind of history the castle would inhabit.

As Ulster entered a period of plantation, rebellion, and consolidation under English rule, Dunluce slipped from being a seat of power into something more symbolic. Authority no longer required clifftop fortresses. It required administration, land ownership, and proximity to roads rather than sea routes.

The MacDonnell family moved their focus inland, building more comfortable residences better suited to a changing political reality. Dunluce, exposed and structurally compromised, was left behind.

Yet it never disappeared.

The Castle as Ruin and Resource.

The ruins built directly onto the cliff.

Throughout the late 17th and 18th centuries, Dunluce existed as a functional ruin. Locals quarried stone from it. Walls were dismantled and reused in nearby buildings. The castle was no longer sacred. It was practical.

This quiet dismantling mattered more than any dramatic destruction. Dunluce was slowly absorbed into the surrounding landscape and economy, its stones redistributed across farms and settlements. What remained did so largely because it was too dangerous or inaccessible to remove.

In this period, Dunluce became something new. Not a home. Not a fortress. A landmark.

Romanticism, Ruins, and Reinvention.

By the late 18th and 19th centuries, attitudes shifted.

The same exposed, dramatic qualities that made Dunluce uninhabitable made it irresistible to artists, antiquarians, and early tourists. The rise of Romanticism reframed ruins as objects of awe rather than inconvenience. Dunluce, perched above the Atlantic, fitted this new sensibility perfectly.

It was painted, written about, and increasingly mythologised. Stories of collapse, ghosts, and doomed inhabitants flourished. The castle became less about what had happened there and more about what it represented: transience, decay, and the limits of human ambition.

This was the point at which Dunluce stopped being a lived place and became a cultural one.

Preservation and Modern Control.

In the 20th century, Dunluce passed fully into state care. Excavation and stabilisation efforts revealed more about the castle’s layout, including evidence of a planned town built nearby by Randal MacDonnell. This town, intended as a modern settlement with grid streets and continental influence, ultimately failed, another ambition undermined by circumstance.

The ruins were consolidated, not restored. Dunluce was never rebuilt or romanticised through reconstruction. Its instability made that impossible.

Today, it is managed not as a monument to victory or empire, but as a controlled ruin. Paths are set back from the edge. Certain areas remain inaccessible. The sea still dictates the terms.

Dunluce Now.

Modern Dunluce exists in tension between access and danger.

Visitors walk the same narrow approach once defended by armed men. They stand in rooms open to the sky. They look through windows that frame only ocean. No other castle on the island makes exposure so explicit.

Crucially, Dunluce has never been fully tamed. Erosion continues. Monitoring continues. The cliff edge still shifts.

This is not a finished historical site. It is an ongoing one.

Why the Story Does Not End.

Dunluce matters after the 1600s because it shows what happens after power leaves.

When authority fades, when families move on, when the political centre shifts elsewhere, landscapes do not reset. They remember. They erode. They repurpose.

Dunluce did not fall into irrelevance. It transitioned from power to warning.

A castle that once controlled the sea now stands as evidence that no structure, however dominant, outlasts the ground beneath it.

And that story is still unfolding.

A Ruin That Refuses Romance.

Dunluce Castle matters because it resists romanticisation. It is not softened by ivy or framed neatly by landscape. It is raw, exposed, and incomplete.

It reminds us that power depends not just on walls and weapons, but on the land beneath them. When that land fails, so does authority.

Dunluce was never truly conquered.

It was undone by the ground it stood on.